Rapoport Weisberg Sims & VanOverloop, P.C. was retained by numerous families who lost loved ones from the tragic crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, a nearly brand-new Boeing 737 MAX aircraft that crashed shortly after takeoff from Addis Ababa Bole International Airport on March 10, 2019. This was the second Boeing MAX crash in less than five months following the October 2018 crash of Lion Air Flight 610, which also involved an activation of the MCAS system. The crash of ET 302 led to a grounding of the entire 737 MAX fleet for nearly two years by civil aviation authorities from around the world.

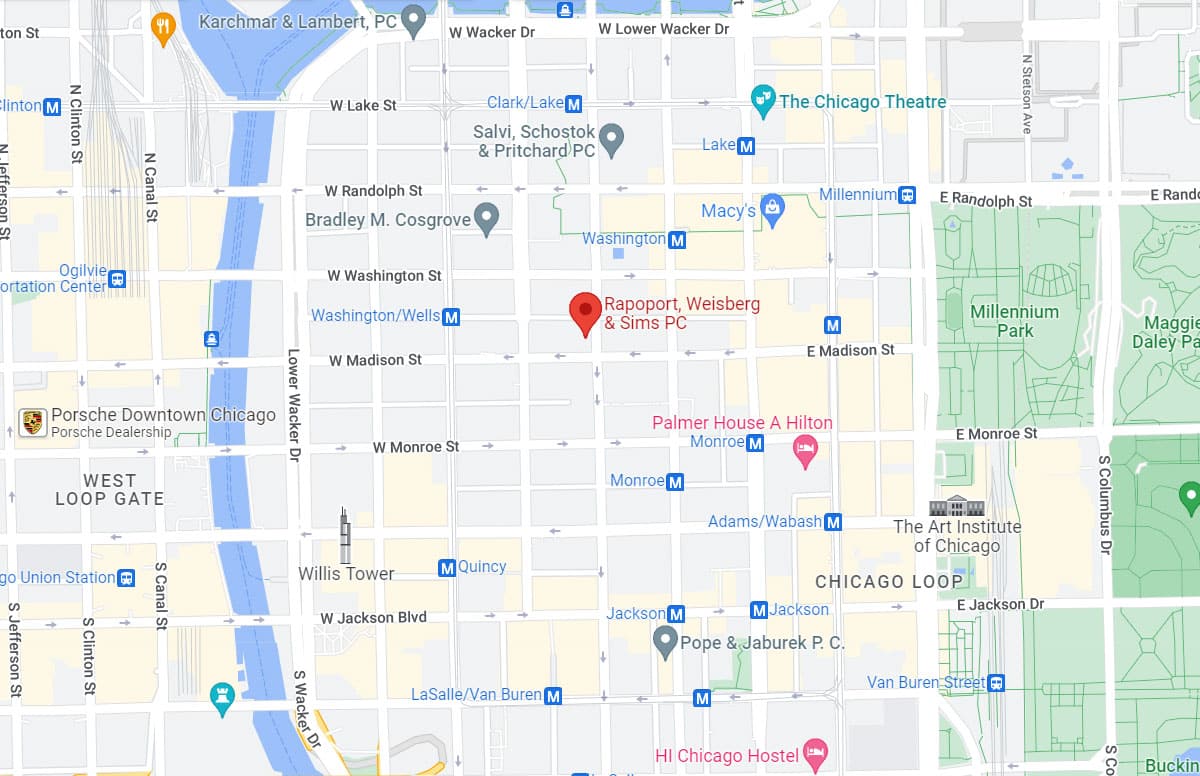

The families of the victims brought civil suits against Boeing in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, which were all consolidated as In Re Ethiopian Airlines ET 302 Crash. Rapoport Weisberg Sims & VanOverloop shareholders David E. Rapoport and Matthew S. Sims were appointed to the Plaintiffs’ Executive Committee charged with leading the prosecution of Boeing related to the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. After years of litigation, Boeing finally admitted that it was accepting responsibility for the crash of Flight ET 302, which caused the deaths of all 157 passengers and crew aboard.

A timeline of the development of the Boeing 737 MAX leading up to the crash and just following it are provided below.

2023

A United States federal judge ordered The Boeing Company to appear in Court to be arraigned on felony charges involving the deaths of 346 passengers and crew aboard Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302.

2022

United States Judge Jorge Alonso selects the first groups of civil cases set to begin jury trials in 2023.

2021

Boeing Charged with 737 MAX Fraud Conspiracy by the United States Department of Justice and Agrees to Pay over $2.5 Billion.

Boeing has been charged with conspiracy to defraud the United States and has agreed not to contest the charges and admits that it engaged in criminal conduct intended to deceive and mislead the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) during the 737 MAX certification process. Under the terms of the agreement with the Justice Department, Boeing will pay a total criminal monetary amount of over $2.5 billion, composed of a criminal monetary penalty of $243.6 million, compensation payments to Boeing’s 737 MAX airline customers of $1.77 billion, and the establishment of a $500 million crash-victim beneficiaries fund to compensate the heirs, relatives, and legal beneficiaries of the 346 passengers who died in the Boeing 737 MAX crashes of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302.

“The misleading statements, half-truths, and omissions communicated by Boeing employees to the FAA impeded the government’s ability to ensure the safety of the flying public,” said U.S. Attorney Erin Nealy Cox for the Northern District of Texas. “This case sends a clear message: The Department of Justice will hold manufacturers like Boeing accountable for defrauding regulators – especially in industries where the stakes are this high.”

The agreement does not address any misconduct of Boeing top corporate officials, although it highlights the conduct of top Boeing flight pilots who chose to repeatedly mislead the FAA in order to elevate profits over safety.

Boeing has now admitted in Court documents that “The purpose of the conspiracy was to defraud the FAA AEG by impairing, obstructing, defeating, and interfering with the lawful function of the FAA AEG by dishonest means in connection with its publication of the 737 MAX FSB Report and its differences-training determination for the Boeing 737 MAX, in order to bring about a financial gain to Boeing and to benefit Boeing Employee-1 and Boeing Employee-2 in connection with the Boeing 737 MAX.” Ongoing civil litigation is expected to highlight further misconduct by Boeing that was not included in the Justice Department agreement.

December 18, 2020

The United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, today released the Committee’s investigation report on the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). This investigation began in April of 2019, weeks after the second of two tragic crashes of Boeing 737 MAX aircraft. Ethiopian Ministry of Transport released its preliminary report into the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. Click here to read the Committee’s report, which includes a one-page executive summary and a six-page overview.

Some of the report’s more significant findings include:

- Boeing inappropriately influenced FAA human factor simulator testing of pilot reaction times involving a Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) failure during 737 MAX recertification testing,

- FAA senior managers have not been held accountable for failure to develop and deliver adequate training in flight standards, despite repeated findings of deficiencies over several decades.

- The FAA continues to retaliate against whistleblowers instead of welcoming their disclosures in the interest of safety.

- The Department of Transportation Office of General Counsel (DOT OGC) failed to produce relevant documents requested by Chairman Wicker as required by Article I, Section I of the Constitution.

- FAA senior leaders may have obstructed a Department of Transportation review of the 737 MAX crashes.

- The FAA repeatedly permitted Southwest Airlines to continue operating dozens of aircraft in an unknown airworthiness condition for several years. These flights put millions of passengers at risk.

March 9, 2020

The Ethiopian Ministry of Transport released its preliminary report into the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302. A copy is available here.

As part of its initial findings, the Ethiopian Ministry of Transport found that:

- There were no technical problems before departure.

- The aircraft weight and balance was within the operating limits.

- Shortly after liftoff, the left angle-of-attack (AOA) sensor started recording discrepant and erroneous values.

- Immediately after the left AOA sensor failure, the left hand flight director pitch command and pitch bars began to display different guidance to the pilots.

- The MCAS erroneously activated numerous times during the flight.

- The difference training between the 737 Next Generation (predecessor aircraft) and 737 MAX was inadequate to inform pilots of the differences in the aircraft.

- The AOA Disagree alert message failed to appear on the aircraft per the design described on the flight crew operation manual.

- The AOA failure detection feature failed to activate.

- Single AOA inputs into the MCAS design made it vulnerable to undesired activation.

- Boeing failed to consider an erroneous AOA input into the MCAS in its Functional Hazard Assessment.

March 6, 2020

The United States House of Representatives Committee on Transportation & Infrastructure released its Preliminary Investigative Findings into the design, development, and certification of the Boeing 737 MAX Aircraft. A copy is available here.

As part of its investigation, the Committee held five hearings on issues related to the 737 MAX. The investigation reviewed over 600,000 pages of records from Boeing, the FAA, and others, and included over 20 official interview with Boeing employees and FAA officials.

The Committee’s preliminary findings identified five central themes that affected the design, development and certification of the 737 MAX, including:

- Production Pressures – Boeing had tremendous financial pressures to complete the 737 MAX program to complete with the Airbus’ A320neo aircraft. This resulted in extensive efforts to cut costs and speed up 737 MAX development and production.

- Faulty Assumptions – Boeing made fundamentally faulty assumptions about critical technologies, most notably the MCAS. Based on faulty assumptions, Boeing designed the MCAS to allow on a single angle-of-attack (AOA) sensor.

- Culture of Concealment – Boeing withheld crucial information from the FAA, its customers, and 737 MAX pilots. This included the existence of MCAS to the pilots, and that the AOA disagree alert was inoperable on almost all 737 MAX aircraft.

- Conflicted Representation – FAA’s current oversight structure with respect to Boeing creates inherent conflicts of interest that jeopardize the safety of the flying public. Numerous Boeing employees granted special permission by the FAA to act on behalf of the agency failed to take appropriate actions to protect the flying public.

- Boeing’s Influence Over the FAA’s Oversight – On numerous occasions, FAA management overruled the FAA’s own technical experts at the behest of Boeing. In these cases, the FAA’s technical and safety experts determined that Boeing designs were potentially unsafe and failed to comply with FAA regulations, only to have FAA management overrule them by siding with Boeing.

September 26, 2019

The United States National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has released a report faulting Boeing for failing to assess how pilots would respond to multiple alerts in the new 737 MAX aircraft. “We’ve identified a gap in the human/machine or human/airplane interface,” said Evan Byrne, the NTSB’s chief of human performance and survival factors in the Office of Aviation Safety, in a press briefing. “We are trying to close that gap as it relates to multiple alerts going off simultaneously.”

Dana Schulze, the director of the Office of Aviation Safety, said Boeing assumed in its testing that pilots would “immediately identify (the MCAS) unintended trim action” and then “immediately take action” to counter it, by using thumb switches on the control column to pull the nose back up and if necessary to hit two cutoff switches and stop all automatic stabilizer movement.

As demonstrated by the crashes and what is currently known about the flight crews’ reactions, Boeing’s assumptions proved wrong. With those distractions in the cockpit— and in the case of the Lion Air flight, with the crew having no prior knowledge of MCAS, which Boeing had omitted from the flight manuals — the pilots did not diagnose the problem they were facing and failed to respond as Boeing expected. When MCAS re-activated repeatedly with just five-second breaks, which was never anticipated in Boeing’s design, it eventually overcame the Lion Air crew.

June 5, 2019:

A new report from the New York Times cites evidence that in the year before the 737-MAX design was completed, Boeing made the now infamous MCAS system more aggressive and riskier than originally designed. Citing interviews with former Boeing test pilots, it appears the original version of the MCAS relied on data from at least two types of sensors. In the original design, the MCAS would activate only in rate conditions, and the corrections made to the flight controls would be subtle.

Unfortunately, Boeing engineers reconceived the system late in the design process. This software rewrite allowed the MCAS to engage much more frequently, and when activated, make aggressive inputs into the flight controls. The final version put into production and aboard both the Ethiopian Airlines and Lion Air planes also relied on data from just a single angle-of-attack sensor, and removed data input from other sensors. In both crashes, the single point of data collection failed, engaging the aggressive MCAS system and sending both planes into unrecoverable nose-dives.

Former and current employees have described a “compartmentalized” approach to the design process, that left different engineers in the dark about design changes being made to related aircraft systems. Apparently, the changes in the MCAS system, including the elimination of failure redundancy, were never disclosed to the Federal Aviation Administration officials involved in determining pilot training needs. Questions about why aggressive changes to flight control systems were made late in the design stage and prior to Boeing seeking approval from the FAA for the new aircraft remain unanswered. These questions and others will be part of the focus in the pending litigation against Boeing.

May 31, 2019: Update

Chicago, Illinois: An order was entered by District Judge Jorge L Alonso consolidating all Ethiopian Airlines crash cases in the United States federal court in Illinois into a single proceeding for purposes of issue consolidation and discovery.

May 24, 2019:

Bloomberg is reporting that Boeing Faces an investigation by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) into whether Boeing made candid and appropriate disclosures to its shareholders as it related to the 737 Max. As reported by Bloomberg:

Boeing has already faced questions about its level of disclosures. It revealed in a May 5 statement that it knew a cockpit alert wasn’t working properly for more than a year before the company shared its findings with airlines or the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration. Boeing made the disclosure to customers and the FAA after the October crash, according to the statement.

Meanwhile, a joint investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of Transportation Inspector General’s Office is continuing to look into the circumstances surrounding the certification of the 737 Max. Bloomberg’s related reporting on the criminal investigation noted that:

U.S. Federal Aviation Administration employees warned seven years ago that Boeing had too much sway over safety approvals of new aircraft, prompting an investigation by Transportation Department auditors who confirmed the agency hadn’t done enough to “hold Boeing accountable.”

The 2012 investigation also found that discord over Boeing’s treatment had created a “negative work environment” among FAA employees who approve new and modified aircraft designs, with many of them saying they’d faced retaliation for speaking up. Their concerns pre-dated the 737 Max development.

In recent years, the FAA has shifted more authority over the approval of new aircraft to the manufacturer itself, even allowing Boeing to choose many of the personnel who oversee tests and vouch for safety. Just in the past few months, Congress expanded the outsourcing arrangement even further.

May 14, 2019:

The Dallas Morning News has reported it has contained exclusive audio from the Allied Pilots Association, the union for American Airlines pilots, confronting Boeing about the new features to the 737 Max in November of 2018 – less than a month after the Lion Air Flight 610 crash and four months before the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302.

During the heated confrontation, one pilot is heard telling the Boeing executives, including Boeing vice president Mike Sinnett, in a stern tone regarding the lack of knowledge regarding the MCAS: “We flat out deserve to know what is on our airplanes.”

Another pilot is heard angrily explaining: “We’re the last line of defense to being in that smoking hole. And we need the knowledge.”

April 30, 2019:

Chicago, Illinois: Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg spoke at the Boeing stockholders meeting and attempted to justify why Boeing installed the MCAS on the 737 MAX, but chose not to disclose its existence to the pilots who would be flying passengers worldwide in the 737 MAX line of aircraft. Muilenburg denied that the two recent crashes of the 737 MAX aircraft were due to any “technical slip” by Boeing.

The worldwide 737 MAX fleet remains grounded while Boeing works on a software update that will significantly change the way the MCAS system functions. At a news conference at Boeing’s facility, Mike Sinnet, the vice president of product strategy and development, announced the redesigned MCAS will be changed to activate on data from both fuselage angle-of-attack sensors, instead of just one. The redesigned system will also only operate once, not multiple times, so that a pilot can always pull back on the control column to counteract the MCAS. It is, at least for now, apparently a better solution to the originally designed MCAS system that failed to provide for any hardware redundancy in the case of a single angle-of-attack sensor failure – surprising since the 737 MAX is equipped with two sensors, which could have provided a redundant source of data if one of the sensors failed.

Chicago aviation attorney David Rapoport, who is representing family members of those lost in the Ethiopian Airlines crash, expressed astonishment at the recent comments expressed by Muilenberg:

“That Boeing won’t own responsibility for the deficient design of its aircraft after two well-qualified sets of pilots at two internationally respected airlines lost control of two different brand new aircraft is sad. Instead of Boeing and its lawyers posturing to defend its weak design choices they should be helping the families of those who died in the crashes. Unfortunately, the job of getting to the bottom of understanding why Boeing made decisions that cost 346 people their lives may be left to the civil justice system.”

What also remains unclear is Boeing’s choice to not ensure 737 MAX pilots appreciated that flight controls could literally be taken out of their hand by an automated system. “Automation surprise” is and has been a known phenomenon in the design of ever-complex aircraft flight control systems. More than a decade ago, experts in aircraft design were warning of the dangers of “automation surprise”, which occurs when aircraft systems were designed in a way that once activated, confounded and overwhelmed flight crews. Boeing’s choice to implement the new MCAS system without warning pilots is an area of extreme concern, and one which has rubbed pilots the wrong way.

As previously reported by Bloomberg, none of the documentation for the 737 MAX aircraft included an explanation of the MCAS system. Southwest Airlines and American Airlines, the two largest American carriers operating the 737 MAX prior to its grounding had pilots unions outspoken about being kept in the dark about the MCAS. The president of the Southwest Airlines Pilots Association stated “We don’t like that we weren’t notified [about the MCAS]”, while the spokesman for the Allied Pilots Association at American Airlines Group, Inc. expressed similar concerns about American Airlines pilots not having been told about the new MCAS system.

April 10, 2019:

A Boeing shareholder lawsuit was filed in Chicago. In this lawsuit Boeing shareholders argue Boeing misled them by hiding what was known about the dangerous design of 737-MAX aircraft in order to generate profits and drive stock prices higher. According to the shareholder lawsuit, Boeing “effectively put profitability and growth ahead of airplane safety and honesty” by rushing the 737 MAX to market to compete with Airbus, while leaving out “extra” or “optional” features designed to prevent the loss of control that occurred in the Ethiopian Airlines and Lion Air crashes.

April 4, 2019

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia’s Ministry of Transport’s Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau’s Preliminary Report on the Ethiopian Airlines crash was released show faulty sensor data led to a series of events causing the Ethiopian Airlines crash. The report, based on flight data and cockpit voice recorder data shows that a faulty angle of attack sensor triggered the MCAS system to activate numerous times, even though the aircraft was not at a dangerously steep angle of attack or at risk for a stall. The crew performed the runaway stabilizer checklist that had been the subject of an emergency publication by Boeing, but they could not regain control of the aircraft. These critical initial findings were made:

The air speed and altitude values from the left-sided sensors conflicted with those from the right side of the aircraft significantly. Because the MCAS system was designed to only receive data from one sensor, even though there were two available, the system erroneously responded to unreliable data the aircraft was nearing a dangerous stall attitude, pushing the nose of the plane down.

Data comparisons show strikingly similar flight trajectories between the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines crashes:

Within hours of the preliminary Ethiopian Airlines crash report being released, Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg apologized and said that the preliminary report released hours earlier regarding the Ethiopian Airlines crash indicated the MCAS played a role in the crashes of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 on March 10.

“We at Boeing are sorry for the lives lost in the recent 737 MAX accidents,” Muilenburg said in a statement. “These tragedies continue to weigh heavily on our hearts and minds.”

April 2, 2019

The United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation formally requested the FAA turn over data related to its investigation into whether the FAA was working too closely with Boeing providing inadequate scrutiny in evaluating the safety of the 737-MAX line of aircraft.

April 1, 2019

Boeing informed the FAA it needs more time to work on the software changes for the 737-MAX and the FAA announced Boeing’s final software improvements will be released “in the coming weeks.” It is rumored the changes will include making a previously optional alert system regarding inconsistent angle of attack sensor data standard equipment.

March 30, 2019: Litigation Perspective

Chicago, Illinois: According to attorney David E. Rapoport, who has been handling major air disaster cases for victims over thirty years, the Boeing 737-MAX story is all too familiar. He explains:

In lawsuits arising out of the DC-10 disaster at Sioux City, Iowa in 1989, two races that occurred in the aviation industry years before the crash led to significant safety compromises that contributed to cause the disaster at Sioux City.

The first race in the late 1960s and early 1970s was between air frame manufacturers Boeing, Douglas Aircraft and Lockheed over who would be the first to get their wide body jumbo jets into the market. The competing aircraft in the race were the Boeing 747, the Douglas DC-10 and the Lockheed L-1011.

In the same timeframe the second race was between jet engine manufacturers General Electric, Pratt Whitney and Rolls Royce. They were in a race to develop and market their early version high-ratio bypass jet engines, which were the engines that made wide-body aircraft possible. The competing engines were General Electric’s CF6-6, Pratt & Whitney’s JT9D, and Rolls Royce’s RB 211.

Due to the races in the marketplace and the lead the 747 powered by Rolls Royce engines had, early model CF6-6 engines were raced to market using critical rotating parts made of titanium manufactured with weak process controls, leading to hard and soft alpha inclusions that could case mid-flight cracking and rotating jet engine part failures.

That is exactly what happened on July 19, 1989, when the fan disc on an early CF6-6 engine failed at cruise altitude due to a hard-alpha inclusion that had been present since the titanium was in ingot form. This failure lead to an uncontained failure of the tail mounted engine, sending its shrapnel through the triple redundant hydraulic lines in the tail area, resulting in loss of all hydraulics, leading to loss of all control surface movement and, ultimately, the crash.

As part of the legal team that prosecuted the Sioux City case, I remember the prominent role these two races played in our civil prosecution of the airframe and engine manufacturers. Similarly here, in the case of the Boeing 737-MAX, the 737 hull was not designed or intended to be a perpetual motion machine. Boeing engineers and managers understood this when they decided at first in response to the Airbus A320neo to develop a long overdue new narrow body aircraft. But then everything changed after Airbus had very good air show sales in Paris and its aftermath in 2011.

Commercial airframe manufacturing programs have historically done poorly when short cited business decisions in a race to control market share, lead to safety shortcuts; and we all know we cannot rely on the FAA to stop dangerous practices when the powerful parties they regulate decide to cut corners to beat their competition in short sighted ways.

March 29, 2019

Initial reports from the Ethiopia crash investigation reveal the MCAS system was engaged just prior to the crash, a known factor in the Lion Air crash.

March 19, 2019

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg wrote an open letter announcing Boeing will soon release a 737-MAX software update and offer additional 737-MAX pilot training.

That same day, the United States Department of Transportation requested the Office of the Inspector General to conduct on audit of the certification process for the 737-MAX series.

March 14, 2019

Boeing announced it will suspend deliveries of new 737-MAX aircraft, but that it plans to continue production.

March 13, 2019

The FAA entered an emergency order temporarily grounding all Boeing 737-MAX aircraft.

March 12, 2019

The FAA issued an advisory mandating design changes for the flight control systems of the 737-MAX 8 aircraft, but otherwise continued to defend Boeing, stating a review “shows no systemic performance issues.” This notwithstanding that the European Union and many other countries had grounded the aircraft. Hours later, Boeing announced a plan to update the flight control systems.

March 11, 2019

China announced it was grounding Boeing 737-MAX aircraft in response to the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines crashes. Over the next two days, the FAA resisted calls to ground the aircraft, claiming there was insufficient evidence to support a grounding.

The United States Department of Justice, under the authority of a previously convened secret grand jury, issued a subpoena related to the development of the 737-MAX series of aircraft.

March 10, 2019

Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, another 737-MAX 8 aircraft, crashed six minutes after takeoff from Addis Adaba. The aircraft impacted the ground at nearly 600 mph, leaving an impact crater 90 feet wide and 120 feet long. All of the 157 people aboard the flight were killed.

Source: Ethiopian Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau Preliminary Report.

January 30, 2019

Just months after expressing condolences for the loss of life aboard Lion Air Flight 610, The Boeing Company announced record revenues of $101.1 billion and order an order backlog $490 billion.

November 28, 2018

The Indonesian Komite Nasional Keselamatan Transportasi (KNKT) released its Preliminary Report into the investigation of the crash of Lion Air Flight 610. The investigation revealed the MCAS system pushed the plane’s nose down 26 times in 10 minutes as the pilots struggled to regain control of the aircraft.

November 19, 2018

In denial, Boeing CEO Dennis Mullenberg argued information about the 737 MAX MCAS system was provided to their airline customers, and he denied that Boeing’s flight crew operations manual was deficient, claiming instead it adequately describes the MCAS relevant function.

November 15, 2018

The United States Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA), the largest American airline pilots’ union, urged the FAA to ensure pilots will now receive all relevant information addressing the “potential, significant aviation system safety deficiency” involving the MCAS system.

November 12, 2018

Aviation Week magazine published a review of the 737-MAX flight crew operations manual which repeats that the manual does not mention the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS).

November 7, 2018

The United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issued an emergency Airworthiness Directive requiring that amended operating limitations and procedures relating to erroneous data from an angle of attack sensor be inserted into the flight manual of each 737-MAX aircraft:

Soon thereafter a Boeing 737 pilot submitted the following scathing report to the United States Federal Aviation Administration’s Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS), which permits pilots to confidentially report their safety concerns to the FAA:

The recently released 737 MAX8 Emergency Airworthiness Directive directs pilots [on] how to deal with a known issue, but it does nothing to address the systems issues with the AOA [angle of attack] system.

MCAS (Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System) is implemented on the 737 MAX to enhance pitch characteristics with flaps UP and at elevated angles of attack. The MCAS function commands nose down stabilizer to enhance pitch characteristics during steep turns with elevated load factors and during flaps up flight at airspeeds approaching stall. MCAS is activated without pilot input and only operates in manual, flaps up flight. The system is designed to allow the flight crew to use column trim switch or stabilizer aisle stand cutout switches to override MCAS input. The function is commanded by the Flight Control computer using input data from sensors and other airplane systems.

The MCAS function becomes active when the airplane angle of attack exceeds a threshold based on airspeed and altitude. Stabilizer incremental commands are limited to 2.5 degrees and are provided at a rate of 0.27 degrees per second. The magnitude of the stabilizer input is lower at high Mach number and greater at low Mach numbers. The function is reset once angle of attack falls below the angle of attack threshold or if manual stabilizer commands are provided by the flight crew. If the original elevated AOA condition persists, the MCAS function commands another incremental stabilizer nose down command according to current aircraft Mach number at actuation.

This description is not currently in the 737 Flight Manual Part 2, nor the Boeing FCOM, though it will be added to them soon. This communication highlights that an entire system is not described in our Flight Manual. This system is now the subject of an AD.

I think it is unconscionable that a manufacturer, the FAA, and the airlines would have pilots flying an airplane without adequately training, or even providing available resources and sufficient documentation to understand the highly complex systems that differentiate this aircraft from prior models. The fact that this airplane requires such jury rigging to fly is a red flag. Now we know the systems employed are error prone–even if the pilots aren’t sure what those systems are, what redundancies are in place, and failure modes.

I am left to wonder: what else don’t I know? The Flight Manual is inadequate and almost criminally insufficient. All airlines that operate the MAX must insist that Boeing incorporate ALL systems in their manuals.

October 29, 2018

Lion Air Flight 610 crashed into the Java Sea 12 minutes after takeoff. All 189 passengers and crew were killed. The Boeing 737-MAX 8 had been delivered new to Lion Air on August 13, 2018 and had flown 800 hours.

June 22, 2017

Boeing announced record aircraft sales at the Paris Air Show, almost entirely due to the 737-MAX.

May 6, 2017

The First 737-MAX series aircraft was delivered to a subsidiary of Lion Air.

March 8, 2017

The United States FAA certified the 737-MAX series.

January 29, 2016

The first Boeing 737-MAX 8 model (the first of the 737-MAX series) completed a successful test flight nearly 49 years after the maiden flight of the first 737-100 on April 9, 1967.

January 25, 2016

The A320neo officially entered service, first being used by Lufthansa.

November 2015

The first 737-MAX rolled out of Boeing’s factory. It was completed years quicker than if Boeing had redesigned an entirely new narrow-body aircraft to complete with Airbus A320neo.

July 2013

The “firm configuration” of the 737-MAX line of aircraft is achieved.

September 2012

The Boeing 737-MAX line of aircraft is first offered for order to customers.

August 30, 2011

Boeing announced it has changed direction from just a few months before and will plan to launch a new engine variant of the 737 powered by the CFM International LEAP-1B engines. Utilizing an older plane design and avoiding an entirely “new plane” avoided a lengthy certification process, as well as expensive new pilot training that would be necessary for a new aircraft type… a cost that would have had to be shouldered by Boeing’s airline customers and might impact sales.

The LEAP-1B engines have a height of 88.8 inches with a dry weight of 6,100 lbs. By comparison, the prior-equipped CFM56-7 series were smaller, at 72.0 inches tall with a dry weight of approximately 5,300 lbs.

According to an engineering professional with design experience on the 737-MAX, reflecting back on that time period, “the timeline was extremely compressed,” the engineer said. “It was go, go, go.”

Another former designer on the team working on flight controls for the 737-MAX said the group had at times produced 16 technical drawings a week, double the normal rate. “They basically said, ‘We need something now,’” the designer said. Meanwhile, a technician who assembled wiring on the 737-MAX said that in the first months of development, rushed designers were delivering sloppy blueprints to him. He was told that the instructions for the wiring would just be cleaned up later in the process.

In order to make the larger diameter and heavier engine fit under the low-slung 737 wing, Boeing engineers relocated the engine housing so that it was higher off of the ground. However, the only way to do this was to move it forward on the airplane. This, in turn, changed the aerodynamics and handling characteristics of the entire aircraft, including the manner in which the aircraft performed at a high angle of attack, such as takeoff. In order to counter-balance these new intrinsic handling characteristics, Boeing implemented the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), which takes the controls from the pilots and pushes the aircraft nose down when a potentially dangerously high angle of attack is detected.

The MCAS relies on accurate data from the angle of attack sensor to swivel the horizontal stabilizer (or horizontal tail) causing the aircraft to nose down.

Shockingly, the MCAS system was designed to only rely on one of the two angle-of-attack sensors. Boeing and the FAA decided the angle-of-attack reading was not critical for safe operation, and as such, an angle-of-attack “disagree-alert” system could be an optional feature, for an $80,000 upcharge.

July 20, 2011

American Airlines announced an order for 460 narrow-body commercial aircraft, including 260 of the newest Airbus A320neo aircraft. This order broke Boeing’s monopoly with the world’s largest airline, and soon after this Boeing changed directions and began development of what would eventually become the Boeing 737-MAX line.

June 23, 2011

At the Paris Air Show, the A320neo set an order record for a new commercial airliner, gathering 667 commitments for a total Airbus backlog of 1,029 units since the launch of the A320neo. Airbus won approximately $72.2 billion of contractual commitments for a total of 730 aircraft, setting a new all-time record for sales by commercial airframe manufacturers at air shows. In the first two days of the show, Airbus sold $26 billion worth of aircraft, compared to just $16 billion in the same two days for Boeing.

February 10, 2011

Boeing Chair and CEO James McNernery announced that Boeing is inclined to wait and design an entirely new narrow-body aircraft to compete with the A320neo, rather than put engines that were too big on the 737 line of aircraft. “We’re going to do a new airplane.”

December 6, 2010

CBS News’ Brett Snyder writes that it does not appear that Boeing will be responding to the release of the A320neo with a comparably fuel-efficient aircraft. The concerns are that the Boeing 737 airframe does not have the physical capability to mount the more fuel efficient, but larger diameter jet engines:

“One of the issues for Boeing is that it takes more work to put new engines on the 737 than on the A320. The 737 is lower to the ground than the A320, and the new engines have a larger diameter. So while both manufacturers would have to do work, the Boeing guys would have more work to do to jack the airplane up. That will cost more while reducing commonality with the current fleet. As we know from last week, reduced commonality means higher costs for the airlines as well… So instead of jumping into the fray with a re-engined 737, Boeing can just wait a few years. It can get the 787 [Dreamliner aircraft design] behind it, wait for the newer engine technologies to fully develop, and then design an entirely new replacement for the 737. While the neo does give Airbus an advantage over Boeing, a brand new 737 replacement would probably put Airbus at a severe disadvantage.

December 1, 2010

Boeing’s main competitor, Airbus, announces the A320neo (“New Engine Option”) family of aircraft, estimated to have 15% increased fuel efficiency compared to other models, paving the way for Airbus to gain a serious competitive advantage over Boeing in the “narrow-body” commercial aircraft market.

2008:

The price of jet fuel reached a peak in 2008, when airlines devoted 40% of the retail price of an air ticket to pay for fuel, versus 15% in 2000. Consequently, in that year carriers retired Boeing 737-Classic series aircraft to reduce fuel consumption; replacements consisted of more efficient Next Generation 737s or Airbus A320/A319/A318 series aircraft. On June 4, 2008, United Airlines announced it would retire all 94 of its Classic 737 aircraft (64 737-300 and 30 737-500 aircraft), replacing them with Airbus A320 jets taken from its “Ted” subsidiary, which had been shut down.

1991-1998: The Boeing 737 “Next Generation”

Prompted by the new Airbus A320, Boeing initiated development of an updated series of aircraft in 1991. After working with potential customers, the 737 Next Generation (NG) program was announced on November 17, 1993. The 737NG encompasses the -600, -700, -800, and -900, and is to date the most significant upgrade of the airframe. The performance of the 737NG is, in essence, that of a new aircraft, but important commonality is retained from previous 737 models.

The wing was redesigned with a new airfoil section, greater chord, increased wing span by 16 ft (4.9 m) and area by 25%, which increased total fuel capacity by 30%. New, quieter, more fuel-efficient CFM56-7B engines were used. The wing, engine, and fuel capacity improvements combined increase the 737’s range by 900 nautical miles (1,700 km) to over 3,000 nautical miles (5,600 km), now permitting transcontinental service. With the increased fuel capacity, higher maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) specifications are offered. The 737NG included redesigned vertical stabilizers, and winglets were available on most models. The flight deck was upgraded with modern avionics, and passenger cabin improvements similar to those on the Boeing 777, including more curved surfaces and larger overhead bins than previous-generation 737s.

The first NG to roll out was a -700, on December 8, 1996. This aircraft, the 2,843rd 737 built, first flew on February 9, 1997. The prototype -800 rolled out on June 30, 1997, and first flew on July 31, 1997. The smallest of the new variants, the -600s, is the same size as the -500. It was the last in this series to launch, in December 1997. First flying January 22, 1998, it was given certification on August 18, 1998. A flight test program was operated by 10 aircraft; 3 -600s, 4 -700s, and 3 -800s.

1978-1991: The Boeing 737 “Classic” Series

Development began in 1979 for the 737’s first major revision. Boeing wanted to increase capacity and range, incorporating improvements to upgrade the aircraft to modern specifications, while also retaining commonality with previous 737 variants. In 1980, preliminary aircraft specifications of the variant, dubbed 737-300, were released at the Farnborough Airshow. The 737-300 was the first “Classic” variant.

Boeing engineer Mark Gregoire led a design team, which cooperated with CFM International to select, modify and deploy a new engine and nacelle that would make the 737-300 into a viable aircraft. They chose the CFM56-3B-1 high-bypass turbofan engine to power the aircraft, which yielded significant gains in fuel economy and a reduction in noise, but also posed an engineering challenge, given the low ground clearance of the 737 and the larger diameter of the engine over the original Pratt & Whitney engines as can be seen in these comparative photos.

Gregoire’s team and CFM solved the problem by reducing the size of the fan (which made the engine slightly less efficient than it had been forecast to be), placing the engine ahead of the wing, and by moving engine accessories to the sides of the engine pod, giving the engine a distinctive non-circular “hamster pouch” air intake.

The passenger capacity of the aircraft was increased to 149 by extending the fuselage around the wing by 9 feet 5 inches (2.87 m). The wing incorporated several changes for improved aerodynamics. The wingtip was extended 9 in (23 cm), and the wingspan by 1 ft 9 in (53 cm). The leading-edge slats and trailing-edge flaps were adjusted. The tailfin was redesigned, the flight deck was improved with the optional EFIS (Electronic Flight Instrumentation System), and the passenger cabin incorporated improvements similar to those developed on the Boeing 757. The prototype -300, the 1,001st 737 built, first flew on February 24, 1984. It and two production aircraft flew a nine-month-long certification program.

In June 1986, Boeing announced the development of the 737-400, which stretched the fuselage a further 10 ft (3.0 m), increasing the passenger load to 188. The -400s first flight was on February 19, 1988, and, after a seven-month/500-hour flight-testing run, entered service with Piedmont Airlines that October.

The -500 series was offered, due to customer demand, as a modern and direct replacement of the 737-200. It incorporated the improvements of the 737 Classic series, allowing longer routes with fewer passengers to be more economical than with the 737-300. The fuselage length of the -500 is 1 ft 7 in (48 cm) longer than the 737-200, accommodating up to 140 passengers. Both glass and older-style mechanical cockpits arrangements were available. Using the CFM56-3 engine also gave a 25% increase in fuel efficiency over the older -200s P&W engines.

The 737-500 was launched in 1987 by Southwest Airlines, with an order for 20 aircraft, and flew for the first time on June 30, 1989. A single prototype flew 375 hours for the certification process, and on February 28, 1990, Southwest Airlines received the first delivery.

After the introduction of the -600/700/800/900 series, the -300/400/500 series was called the 737 Classic series.

1965-1978: Original Boeing 737 Development

The Boeing 737 was developed between 1965 and 1967. On December 15, 1967, the Federal Aviation Administration certified the 737-100 for commercial flight, the first aircraft to have, as part of its initial certification, approval for precision instrument approaches and landings with a decision height between 98 to 197 feet. One week later, the 737-200 was certified by the FAA.

Lufthansa was the only significant customer to purchase Boeing 737-100 series aircraft and only 30 737-100s were produced because the lengthened -200 was widely preferred over the -100 by airlines.

The engine chosen for the 737-100 and 737-200 programs was the Pratt & Whitney JT8D-1 low-bypass ratio turbofan pictured below. This engine type was used in some Boeing 727 aircraft and this small profile engine is pictured here:

Unfortunately, Boeing 737 sales were low in the early 1970s and, after a peak of 114 deliveries in 1969, only 22 737s were shipped in 1972. However, the US Air Force saved the program by ordering T-43s, the military version of the 737-200.

1964

In 1964, during the first decade of the civil aviation jet age in America, the Boeing 737 was conceptualized as a lower-cost twin-engine passenger airliner derived from the four-engine Boeing 707 introduced in 1958 and the three-engine Boeing 727 introduced in 1963.